Expanding Access and Choice

BRINGING CARE CLOSER TO HOME

From the Desk of

As you meet Mama Riziki and Mbodze from Kenya and Marta from Mozambique, learning about their lives and experiences, we invite you to also zoom out to think about how “bringing care closer to home” can be a foundational feature of resilient health systems.

Dear Maverick Community,

What a pleasure to introduce the second ISSUE for the Maverick Collective! In this bi-monthly intellectual indulgence – as Rena so nicely teed it up in the launch – we’d like to engage your hearts and minds in both the personal and the conceptual.

As you meet Mama Riziki and Mbodze from Kenya and Marta from Mozambique, learning about their lives and experiences, we invite you to also zoom out to think about how “bringing care closer to home” can be a foundational feature of resilient health systems.

With the Sustainable Development Goals only nine years away, more than 75 national governments in lower and middle-income countries, like Kenya and Mozambique, have committed to advancing toward quality healthcare for all, without financial hardship, also known as Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

But health system strengthening paths to UHC can often be designed from the top-down, not meeting people where they are, particularly the poor and vulnerable.

How can we work with national governments and Ministries of Health to design a different path? A consumer-powered path, embedded into national policy, that meets Mama Riziki, Mbodze, and Marta in their communities or in their homes where possible – where community health workers can deliver essential services and assist with transitions toward quality self-care diagnostics, devices, and drugs?

This ISSUE is brimming with insights and reflections on these questions, including some wise-beyond-her years thoughts from guest editor Stasia Obremskey’s daughter, Grace, and personal social justice considerations from guest editor Ann Morris.

Dig into the Master Class, enjoy this immersive virtual experience, and know how much we thank you for your insatiable curiosity, support, and commitment to transformational change.

Warmly,

Maverick Beat:

EXPANDING ACCESS AND CHOICE

Tune in to Episode 2 of Maverick Beat where, over the course of two segments, we spotlight "Project Riziki"in Kenya and "Transforming the Delivery of Injectable Contraceptives" in Mozambique. You can explore more in the content below including Ann and Stasia’s “journals,” stories from Sara, photos, and more.

Expanding Contraceptive Options for Women in Kenya through Task Sharing

Maverick Beat | Ep.2 Part 1: Project Riziki 14 mins

When we met Mbodze at her home in Chasimba village in Kilifi County, the married mother of 19 children indicated that it had never been her wish to have so many children:

"Providing for these children hasn’t been easy, [...] it’s a day-to-day struggle."MBDOZE’S STORY

By Ezra Abaga, Corporate Communications, PS Kenya

For Mbodze Munga Chiro, uptake of family planning not only addressed her fear of getting pregnant again but also gave her a chance to concentrate on raising her large family and ensure her children went to school. Previously in the community, her family faced ridicule from friends and neighbors for having many children she couldn’t provide for.

When we met Mbodze at her home in Chasimba village in Kilifi County, the married mother of 19 children (firstborn is 34 years while the last born is 1 year 3 months) indicated that it had never been her wish to have so many children. She felt she had no control over getting pregnant. “Providing for these children hasn’t been easy, considering we don’t have a regular source of income and only depend on small-scale farming and help from well-wishers; it’s a day-to-day struggle. We can’t afford meals or have enough beds for all of them; some have to sleep at neighbors’ houses,” stated Mbodze.

Before her sixth child, a friend who had witnessed Mbodze’s plight advised her to consider using a family planning method to prevent her from having more children. Taking the advice, she went to the clinic where, after undergoing counselling and other pre-family planning tests, she was found unfit for the particular method available at the clinic due to being overweight. Frustrated because there was no follow-up system from the clinic, Mbodze gave up on family planning.

A visit by a Community Health Extension Worker after her 19th child, made possible through Project Riziki, enabled Mbodze to better understand her options and ultimately led to her decision to start a family planning method. She had not reached the age of menopause and chose not to get pregnant again. Following the discussion with the Community Health Extension Worker, Mbodze visited Chasimba Health Center where, after counselling and testing, she was found fit to take a family planning method. Currently, family planning enables Mbodze, despite the related challenges, to work hard and ensure her children are well-fed and go to school without having to worry about a new pregnancy.

- 8,287 women accessed family planning services through Community Health Workers

- 720 Community Health Volunteers Trained

Bringing health information and services directly to consumers is a quiet revolution that is disrupting healthcare systems worldwide. This is one of the most exciting public health developments of our time.Ann Morris

When Project Riziki started in Kilifi County, Kenya in 2017, only 3 out of 10 women of reproductive age had access to modern family planning methods, and almost a quarter of expecting mothers were aged 19 or younger.

Project Riziki set out to prove that underserved women in remote rural counties could be reached with long-acting contraceptives through trained Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs). CHEWs were trained to provide women with a full range of contraceptive options, including implants, through local outreach events and by going door to door. This model optimizes the use of limited medical staff while providing more access for women in more rural and remote areas. Project Riziki’s success resulted in Kilifi County committing to continue the program. The project team continues to advocate for a national policy change to allow scale up throughout Kenya.

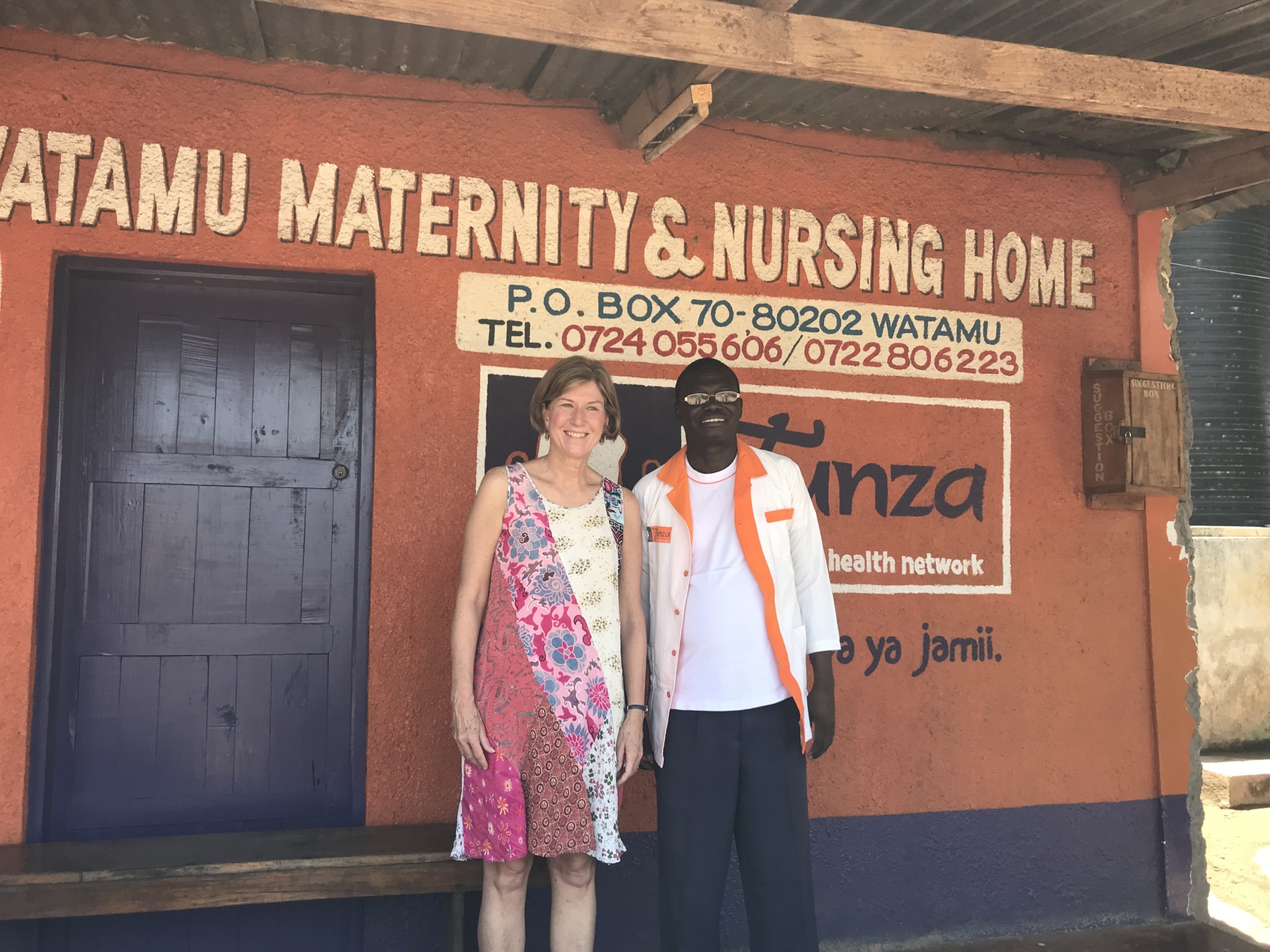

A memorable photograph

This community health outreach event was the first time I got to see a CHEW in action. As women waited their turn to get family planning services, Dennis Baya told me how excited he was to be trained to insert implants. In the past, he said, he was frustrated because he could educate women about implants but often they faced insurmountable obstacles to getting to a clinic to obtain one. Now, he told me proudly, he can provide an implant to a woman who wants one on the spot – whether at an outreach event, a community location or door to door. I will never forget his enthusiasm, professionalism, and dedication.

A memorable meeting with Sara

I had the privilege of meeting “Mama Riziki” on both trips. She was expecting her 10th child when we first visited her, and the despair on her face – from not being able to feed or educate her children, from having no control over her own body – was searing. We made her our “Sara” and named the project after her. When I saw her 18 months later, she was a different person. She had gotten an IUD and found her voice as a family planning champion in her community; the despair had been replaced by hope.

Favorite cultural experience

My husband and two daughters joined me on my second trip to Kenya, and we enjoyed some sightseeing in Nairobi before travelling to the project. Feeding the giraffes at the Giraffe Centre was touristy but delightful. It’s hard to beat one of these beautiful creatures sticking out its giant tongue and taking a food pellet from your hand – or even from between your teeth!

What I learned

I learned the degree to which I was unaware of my privilege, both as a white person and as a person of wealth. I also learned I have an unhealthy dose of “white saviorism” in me. This knowledge has come slowly through my engagement with Maverick and through my personal anti-racism work.

1/4

Creating a Cost-Recoverable Model for the Distribution of Sayana Press in Mozambique

Maverick Beat | Ep. 2 Part 2: Delivery of Injectable Contraceptives in Mozambique 13 mins

Marta wanted the opportunity to choose if and when she had any more children. Her priorities now are the two she already has. Luckily, she lived in a village three hours north of the capital of Mozambique that was served by community health workers (CHWs) [...]The toddler peaked around the corner to gaze at the strange women sitting with his mother in the unfinished room of his house. His father sat in the adjacent room watching a local soccer match on TV. The toddler went back and forth between the two rooms, as his big brown eyes took in one very familiar scene, and one that was very strange to him.

Marta, the mother of the toddler, had another six-year-old child and wanted the opportunity to choose if and when she had any more children. Her priorities now are the two she already has. Luckily, she lived in a village three hours north of the capital of Mozambique that was served by community health workers (CHWs) who shared information with her on various family planning methods and provided her with a choice of condoms, oral contraceptive pills and, most recently, Sayana Press, an injectable contraceptive that combines the drug and needle in an easy to use cartridge and lasts for three months.

My sixteen-year-old daughter, Grace, and I were two of the strange women sitting with Marta that afternoon. We were in Mozambique to listen and learn about the challenges and opportunities for introducing Sayana Press into several rural and urban areas of the country.

Grace and I are members of Maverick Collective, an international group of women that are committed to investing in women and girls in developing countries with our partner Population Services International (PSI). Working with the PSI country office in Mozambique, we developed and funded an innovative pilot project to test three key assumptions:

- With training and supervision, Sayana Press could be safely administered to women by community health workers rather than doctors or nurses.

- Women in Mozambique would be willing to pay a subsidized price for any method of contraception and a service fee for a home visit by the CHW.

- This network of CHWs, clients and their transactions could be tracked by two way communications facilities through a proprietary SMS network called Movercado.

That day, Grace and I tagged along with Ilda, a community health worker, as she made her rounds to several villages. All of the clients she saw that day had first been counseled and screened by a nurse at a Tem Mais clinic in a nearby village. Tem Mais clinics are private-sector family planning clinics where clients pay a subsidized price for health care. After counseling on various family planning methods, the clients I visited that day had selected Sayana Press as their choice of method.

PSI is developing the Tem Mais clinics as a alternative to the public health centers. In Mozambique and other countries around the world, PSI is creating consumer demand for high quality healthcare in the private sector. As rising wealth allows consumers to purchase goods like flat screen TVs, motorbikes and other “luxury” products, these same consumers will demand high quality health services and be willing to pay for them.

Every Tem Mais clinic has 15-20 community health workers assigned to the clinic. The CHWs are all well respected women in the community who receive compensation for referring clients to the clinic. These women also receive extensive training on counseling for all family planning methods and clinical instructions on how to safely and effectively administer a Sayana Press injection.

As Grace and I watched the toddler dart back and forth between the two rooms, Ilda and Marta talked about her next injection of Sayana Press. Ilda underlined that this method did not protect against HIV transmission. Marta asked for and received both male and female condoms and Ilda demonstrated the proper use of the female condom. Once the counseling session was over, Ilda washed her hands, swabbed Marta’s upper arm with an alcohol pad and injected the small needle into Marta’s arm, pushing down on the drug-filled well for five seconds.

After safely disposing of the spent cartridge. Ilda picked up her phone and sent an SMS message to the network to record her visit, noting the date and Marta’s telephone number. In a few moments, Marta’s phone buzzed and the network sent back a 4-digit code. With this code, Ilda confirmed the visit and the network automatically recorded when she would need to return to the village to administer the next dose. This SMS network, called Movercado, sends reminders to Marta about when to expect her next visit and allows for Marta and Ilda to communicate between visits if questions come up. Finally, as we were preparing to leave, Marta paid Ilda 30 Metical (20 Metical for Sayana Press and 10 Metical for the home visit). This is the equivalent of about fifty cents in US dollars.

As we departed the little boy ran to his mother and once safely in her arms, waved goodbye to us. During that home visit, Grace and I had seen the three innovative elements of our project in action: administration of Sayana Press by the CHW, payment for a home visit, and the Movercado network recording the transaction.

The addition of Sayana Press to the menu of family planning options for women like Marta should help increase the contraceptive prevalence rate in Mozambique. The government’s goal is to reach 25% by 2020. In order to achieve this goal, additional short and long term methods will need to be available as well as access to public sector and private sector facilities and home visit options for women to receive their care. Most importantly, we need to ensure that a timely and reliable supply of Sayana Press continues to be available for women who have made this their choice of contraception. The Gates Foundation and others have negotiated a global price of $.85c per Sayana Press injection to select countries. This affordable option has tremendous possibility for women in Mozambique.

- 284,000 Women reached by Community Health Worker's sensitization sessions

- 34,145 Women received the DMPA-SC implant

The two most important things you can do for the world are to educate women and then to give them the tools to manage their fertilityStasia Obremskey

With the goal of reducing unmet need for family planning, PSI Mozambique began this project in September 2016 to develop a cost-recoverable model to improve access to modern contraceptive methods in peri-urban and rural areas through a community-based distribution (CBD) approach. One method that would be introduced for the first time in Mozambique was the injectable contraceptive, DMPA-SC, administered at the village level by community health promoters to women of reproductive age and adolescent girls. Through a fee-based system of community-based distribution, the project leveraged entrepreneurship among community health promoters (CHP) and used technology to connect clients with CHP to bring access to modern contraceptives closer to Sara. This project was viewed as a first step in getting the government and Sara comfortable with the goal of self-administration of the injectable, which was successfully approved by Mozambique in February 2021.

An unexpected moment

My daughter Grace and I arrived in Mozambique over the weekend and wanted to have a few days to explore Maputo and the beautiful beaches in the area before we met our project team. We spent a day touring Maputo and then took a boat out to the peninsula to enjoy a day on the beach. We were sitting on beach chairs by the ocean reading and dozing when a freak wave rolled in and washed us and all our belongings out into the sea! Luckily, the hotel staff was nearby and managed to rescue my bag which had washed out to sea with our passports, money, telephones and jewelry in it. We were washed into bushes along the shore—shocked, but otherwise OK. The hotel had a beach camera which recorded the entire event, so we got to watch it over and over! We recounted our adventure to the country project team the following day and they were also on the beach near Maputo and experienced the rogue wave as well. Several phones and beach towels were also washed out to sea.

A memorable meeting with Sara

When we visited Mozambique, our project was using community health promoters to educate women about various methods and, if selected, inject a 3-month contraceptive, DMPA-SC, to women in their home. The health worker would return every three months for a subsequent injection. We had the opportunity to accompany one of the health workers on her visits to re-inject a woman. This allowed us to meet and see where “Marietta” (Sara in Mozambique) lived and gain a better understanding of her needs and environment. It was a privilege to be welcomed into her home to observe this interaction between the health worker and Marietta and see the health service provided where Marietta needed them. We literally met Marietta where she was!

Grace’s reflections after a visit to a school in Maputo

Monday, March 13; Visited Noroeste 1 Secondary School in Maputo, the capital city of Mozambique. The school enrolls about 6,000 boys and girls from grades 8 to 12, who attend classes in morning, noon and night shifts. Situated in the corner of the common area was a Tem Mais clinic, a small, square room where a trained nurse administers several different types of family planning methods to female students throughout their school day. Wearing distinct green T shirts, identifying them as trained Peer Educators, graduates of the school, mill around outside the clinic while teenage girls in groups of two or three approach them with questions about sex, relationships, and birth control. We sat down with a group of twenty or so girls to talk about family planning, relationships, parental guidance- or lack thereof- and menstruation. The school has no integrated Sex Education curriculum, but students seek information from their biology textbooks, parents, peers, the internet, and the HIV and STI workshops conducted on campus by outside experts. The girls- all roughly around my own age- all had varying levels of knowledge about their own reproductive health. One girl mentioned that she was on birth control at her mother’s request, while a younger student told me, when she started her period, her mother’s sole words of wisdom were: “from this day on, all men are snakes”. Many of the students were well-versed in the different methods and effectiveness of birth control. Compared to the two high schools I’ve attended, I was amazed that the on-campus clinic in Maputo offers everything from emergency contraceptive pills to long-term hormonal implants with the full support of school administrators and parents! Despite the varying levels of information surrounding reproductive health, the girls unanimously agreed on one thing- no one was interested in getting pregnant anytime soon. As one girl put it, they all had “too much in front of them” to get sidelined by an unplanned pregnancy.

1/3

Expanding Access and Choice

In this Master Class we will introduce Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as the aspirational goal our projects and overall operations are working towards and Health Systems Strengthening as the way to achieve it. We focus on how we build stronger health systems for the consumer using a community-based approach.

In this Master Class, we will learn:

- Strategies for unlocking and creating catalytic changes in health systems and understanding the current barriers.

- Why community-based work is an essential component of health systems strengthening and requires attention and investment.

- Successful models of community-based approaches to healthcare delivery and what it means to bring care closer to consumers.

Keynote Speaker

Project Team

Moderator

Heart Homework

Dig deep and learn more -- in your own time and at your own pace.

-

WATCH: Imact Utopia — What is UHC?

We all have some notion of UHC, and the countless acronyms and terms we use when talking about global health but, how well can we explain them to people who have never heard of them? If you are looking for low entry resources, these are just right for the task!

-

READ: COVID-19 and UHC

Necessity is the mother of innovation. While 2020 was no doubt a shock to health systems worldwide, it revealed some vital pathways to achieving UHC.

-

LISTEN: Pandemic-Ready Health Systems

Public health preparedness, security, and resilience strengthen health systems. They are also key components of UHC. In this episode of The Elder’s Finding Humanity Podcast, Mary Robinson and Gro Brundtland discuss how UHC is key for pandemic preparedness and tackling health inequality in the time of COVID-19.